A REMOTE location, whole-of-farm connectivity solution is helping drive productivity and efficiency improvement on Murchison House station, 650km north of Perth near Kalbarri in Western Australia.

Calum Carruth and wife Belinda run cattle and rangeland goats on Murchison House. Mr Carruth outlined the project during a digital forum held as part of MLA’s annual meetings in Canberra this morning.

Calum Carruth from Murchison House Station, Kalbarri, WA

The first phase of the project has concentrated on remote stock water monitoring, but future phases will add to the technology’s impact through automated mustering and other features.

In terms of cost savings, Mr Carruth estimated that in its first year, the project had already saved him $25,000 in vehicle running costs and maintenance alone in monitoring waters. “It’s not going to take long to pay for the whole system – and that’s without adding in the fact that my staff can now do other things, rather than doing water runs three times a week ,” he said.

“It’s certainly going to give us efficiency and productivity bonuses as well.”

Since September, the Carruths have been working with agtech provider Origo.farm to develop tailored technology solutions for Murchison’s operations.

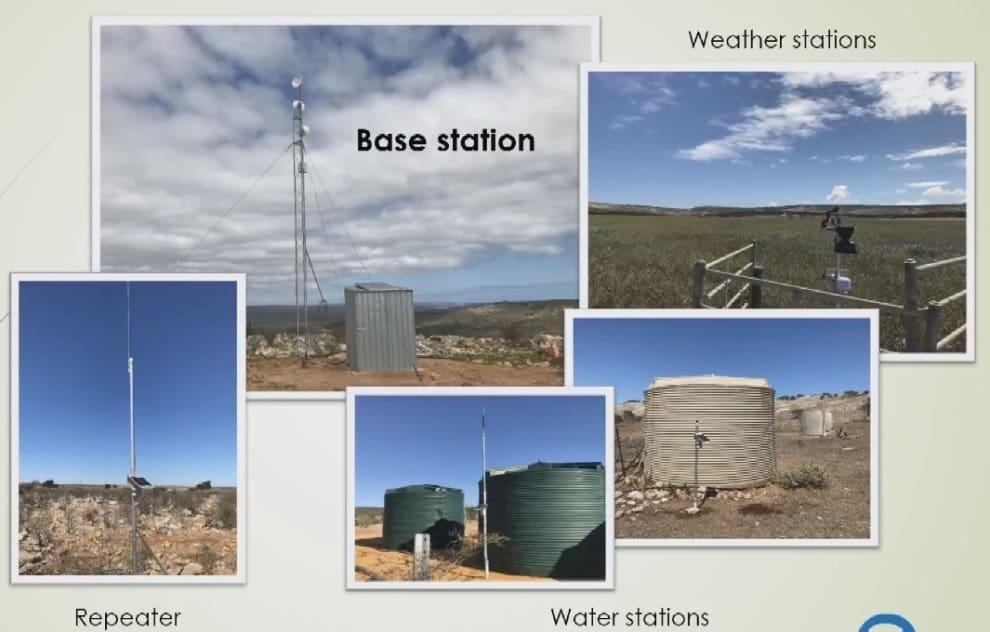

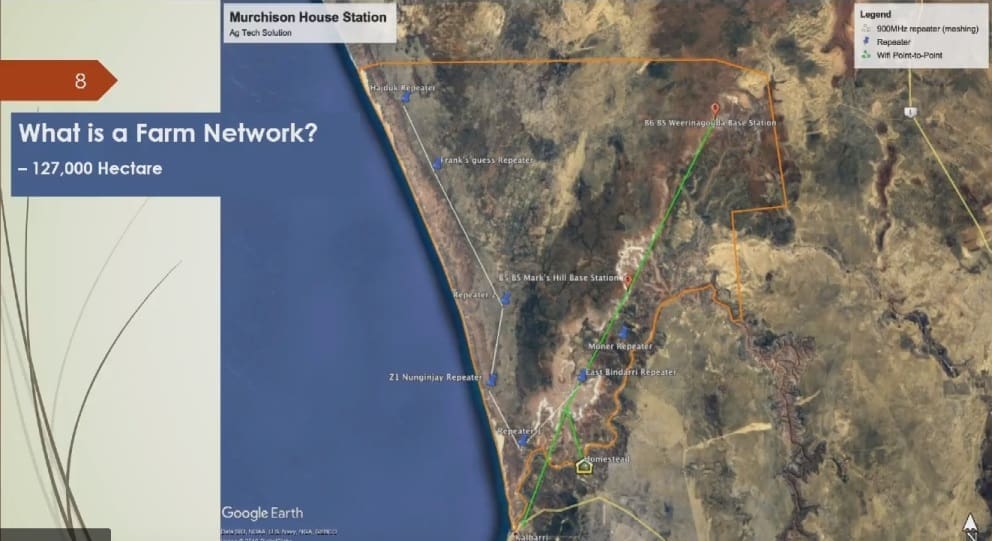

In March, the MLA Donor Company in cooperation with Origo.farm began supporting the project to develop a remote location, whole-of-farm connectivity solution, based on a point-to-point wifi network, based on 900Mh feeds out to a series of sensors, that can be rolled out across other remote properties. The project is supported by matching Federal Government R&D funding.

Murchison House covers 140,000ha, including the ancient limestone Toolonga escarpment, a 150-million-year-old former coral reef that rises 180m above sea level and forms the ‘backbone’ of the property. The terrain is rugged, spectacular and varied. What it’s not, however, is ‘digital friendly’.

“For 20 years, people have been promising things in agtech, but not a lot of technologies had been delivered. But it really has matured very quickly in the last few years,” he told the forum.

Mr Carruth last year contacted Annie Brox from Origo.farm, after learning about her company installing full broadband connectivity across a smaller farmimg application further south, at Mingenew.

“At the time we had no connectivity over most of the station,” he said.

“There were a couple of high spots where you could pick up a mobile phone signal, but not many. Our data was restricted to 50GB of peak time download a month – our son could use that up in one school holiday afternoon of gaming. We had frequent drop-outs and speed tests showed our download speeds were much slower than advertised.”

Origo.farm’s first task was to connect the homestead to fast NBN broadband. They did this by installing a secondary node at a friend’s house in Kalbarri 12km away, then transmitting the signal to a receiving tower on top of a hill at the station, down to towers at water tanks, and on to the homestead.

“The homestead is in a big hollow – only 8m above sea level – so we had to send the signal around the hills,” Mr Carruth said. “We now have fast broadband to the homestead and connectivity around what we call the ‘home paddocks’, or ‘the farm’.

“This gives us unlimited data and the speeds are the same as people on NBN fixed line services in Kalbarri. The NBN isn’t great – my mate in Cambodia has five times our download speeds – but we can now run the station as if we are living in Kalbarri.

“The rest of the station is over the range, which is about 150m high, so we’ll have to get over that to send signal out the back.”

The system installed is independent of the major Telcos, or the internet, with data running direct back to a server at the homestead.

“The data belongs to me – nobody else gets to see it or analyse it, and if the Telstra signal or internet goes down, it all still works. The graphs are very precise, and at a glance, I can see a trend. Its so easy to use,” Mr Carruth said.

Stage one: remote water monitoring and management

As well as accessing fast broadband at the homestead, the Carruths initial goal was to improve on-farm efficiency by allowing remote monitoring of the station’s water points, and remotely controlling pumps. Sensors run 24/7, with downloads each minute.

In summer tanks and water points are checked three times a week, involving a 250km, five-hour round trip each time, over punishing terrain, often in 45-degree heat.

“Vehicle maintenance is a huge cost and, if nothing is actually wrong with the water, you’ve wasted five hours, so it’s quite inefficient.

The couple are now finishing stage one of the project, installing water level sensors and flow meters on four tanks in the home paddocks. Two remote weather monitoring stations have also been installed: one in the main cropping paddock and one at the homestead.

The next phases of the water monitoring project will require connectivity to the farthest water points, 52km to the east, along the Toolonga escarpment, and 56km north, along the coast (see map).

“Once all the water points are connected we’ll only go out to check when something is wrong. The software will establish a baseline of what our cattle and goats usually drink, then it will recognise when something is out of kilter and send an alert to our phones,” Mr Carruth said.

“Not having to go out there three times a week in summer means I can target my crew to do a job, like fencing, that might make some money instead of just spending it.”

Stage two: remote livestock monitoring

Mr Carruth has identified mustering as another area where connectivity could improve efficiency, safety and cost-effectiveness.

“The next stage after water will be remote cameras and automatic gates for monitoring and managing livestock,” he said.

“Our furthest yards are 65km from the house. The plan is to use cameras to monitor the number of goats in an area, and then use the same signal to remotely open and shut gates, which would allow us to target our musters more efficiently.

“Mustering costs are quite dramatic, especially when you get together a light aircraft, a helicopter and half a dozen motorbikes, and you don’t catch anything. And every time you jump on a motorbike to chase goats you’re risking someone falling off.

“If you can look through a camera lens and say ‘there’s no goats there today, let’s not bother, we’ll carry on fencing instead’, that’s saving you exposure to risk and using staff time more cost-effectively.”

Future applications might extend to facial recognition technology to identify wild dogs, he told this morning’s digital forum.

Origo.farm’s Annie Brox said working closely with the Carruths to understand their particular challenges, as well as the technology’s potential application to livestock management had been critical to the project’s success so far.

“Up to this point we had been working with mixed grains and livestock farmers in WA,” she said.

“The Murchison House project means we can do R&D to ensure livestock producers can use tools that are common in other industries. For us, its about saving producers’ resources and time, and assist in creating sustainable red meat operations for the future.

“Having producers like Calum and Belinda to work with is crucial. We need reference farms and producers who are willing to be part of the R&D and share their experiences to enable both the livestock and agtech industries to learn and experience.”

Ms Brox said solution providers needed to “do the hard yards” and field test solutions on-farm.

“I have to emphasise that you really need to be there, testing and learning,” she said.

“Murchison House Station is challenging, and this is helping us to develop the ‘right stuff’: systems that are fit-for-purpose, rugged and priced in such a way that the livestock industry can take full advantage.

The project on Murchison initially planned to use Wi-Fi transmitters but the units were not up to it. Instead, a 900MHz meshing radio system is now used, which is much better at covering the broken limestone landscape.

Apart from Origo.farm’s Intellectual Property (electronics and software), everything is off-the-shelf and easily sourced from local hardware and irrigation stores.

Old windmill towers and towers from an old shortwave radio system are used as repeater towers.

Serviceability is crucial in harsh environments. All wires needed to be inside pipes or conduits to be protected from vermin and birds, as well as sunlight Mr Carruth said. Even the best cables would not stand up to galahs.

HAVE YOUR SAY