A TECHNOLOGY originally developed for use in provide monitoring of calving for intensive dairy use is being used to underpin a large trial in northern Australia seeking to better understand reasons for calf loss.

During a Beef Connect webinar hosted by FutureBeef and Beef Central earlier this week, NTDPI&R principal livestock research officer Tim Schatz stepped-through progress and early learnings from the CalfWatch project.

Calf loss during the first two weeks of life alone, has been estimated to cost the northern Australian beef industry more than $54 million annually.

The earlier CashCow project, recording data on commercial properties across northern Queensland, the Northern Territory and northern regions of WA found that the northern forest zone had median calf loss of 13.5pc, ranging from 9.4pc in the top 25pc, to 19.2pc in the bottom quarter. In the southern forest region of southern Queensland, results were much lower, with a median of 4.6pc calf loss. This figure, alone, suggested there was a lot of scope for improvement in regions further north.

A separate NT project focused on heifers calving for the first time showed a calf loss across 11 commercial properties surveyed averaging 22pc, and ranging from as high as 34pc on a site near Darwin, to 12pc in a herd near Alice Springs.

Mr Schatz said the figures above tended to under-estimate the problem, because calf losses were calculated on records from preg testing to weaning – not just the first two weeks of life.

His presentation was based on a project on Manbulloo Station near Katherine, using 200 Brahman females run in a 2215ha trial paddock. He pointed out that in reality, northern breeders were typically run in paddocks far larger than this.

“In the heifer trial, calf losses tended to be greatest in bigger breeder paddocks. That got us wondering about paddock size, and distance to water. If heifers are calving a long way from water, leaving their calf to go and have a drink, does that create further problems with calf loss? If so, it may really change the economics on reducing paddock size, and intensifying waters – not only to get more even grazing, but to reduce calf loss.”

“But the point is, at the moment we don’t know.”

Hence the CalfWatch project to try to better understand the causes of losses that are occurring.

In the past, traditional measures were used, including observation. In order to do that, pregnant females would have to be in a fairly small paddock, unlike many in northern Australia.

Observation can also change a female’s behaviour, and even contribute further to the problem.

Another challenge with calf-loss studies has been in finding the dead calves for post-mortem study to try to determine the cause of death.

“If we had a method of remotely monitoring calving on an extensive scale, it would allow us to gather data that previously was not possible to collect,” Mr Schatz said.

“It would potentially be a game-changer in the study of calf-loss in extensive areas, and help us identify solutions to reduce the problem.”

Dr Raoul Broughton prepares calving sensors for insertion in Brahman females used in the trial

The CalfWatch project uses a new technology to find out where and when calves are born, and from that, where, when and why they die.

Mr Schatz said the initial project was as much about developing the remote monitoring technology, as about gathering the data.

The technology in use was adapted from calf-loss project work carried out at the University of Florida led by expat Australian, Dr Raoul Broughton.

The Florida project adapted birth sensors developed by Medria Technologies, used mostly for ‘barn-system’ intensive dairy work – a very different environment from that proposed for the NT project.

Coming up with systems to use the sensors in much bigger areas was one of the project challenges. The sensors, using ‘spider legs’ (see image), are inserted into the vagina of pregnant cows, up to four months before they calve. The sensor is expelled when calving takes place, and the rapid change in temperature causes them to start emitting a UHF signal that is picked up by a series of antennae mounted on towers, creating a low-power wireless area network. Mobile phone reception in the areas was either very poor, or non-existent.

Those signals are transferred via gateway, through the internet to servers, a calving alert is sent, and the result is viewable on a website.

Once we came up with ways to increase the area that could be covered with the sensors, using ‘bush engineering’ to construct low-cost, but functional receiver towers powered by solar panels. Each tower has a read range of about 1.8km.

Each of the four fully-equipped towers (see image) needed to cover the paddock worked out at $9500 each, and the sensors cost $177 each, but can be re-used.

Each of the four fully-equipped towers (see image) needed to cover the paddock worked out at $9500 each, and the sensors cost $177 each, but can be re-used.

One of the challenges in the pilot study phase proved to be simply finding the expelled sensors after calving, due to paddock size.

“It reinforced that we needed a way of finding these birth sites, when we scaled up to bigger paddocks,” Mr Schatz said.

While the sensor manufacturer indicated at one point they were considering offering GPS chips in the sensors as an option, this was never provided due to lack of market demand. Having GPS coordinates for an expelled sensor would have solved all the problems, but given the primary use in US dairy herds, there was little demand for it.

The solution was to add a satellite-linked GPS tracker collar to each cow, so it could be roughly determined where she was when the calving alert was sounded from the expelled sensor.

To be of any value, each collar had to ‘ping’ at least every 15 minutes, with data accessible in in ‘real-time’ to have any chance of finding the expelled sensor. Some GPS collars only ping four times each day, making them of little value, given the female could move a large distance after calving before being located.

Secondly, the collar batteries needed to last at least four months, to align with the insert of the sensors around four months before calving. At the time, the only company that could meet the project requirements was Smart Paddock, an Australian company based in Victoria.

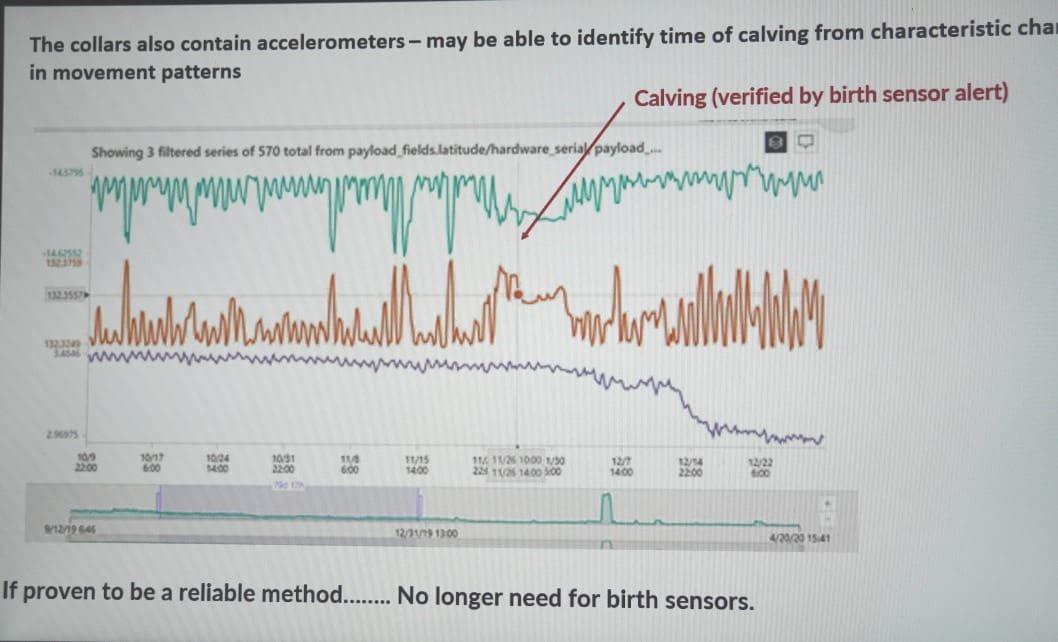

The collars also contained accelerometers, which are showing promise to be used to identify time of calving from characteristic changes in animal movement patterns (see image).

“It is our hope that we may in future be able to use this accelerometer data, instead of sensors, to identify time of calving – less invasive, and removing the need for one set of technology,” Mr Schatz said.

In the main trial, GPS tracking collar birth sensors were inserted in 200 pregnant females last August, in what was at that time the largest use of GPS tracking collars known.

“Basically, the technology worked very well,” Mr Schatz said. “We received alerts from 85pc of the birth sensors that were expelled, and if the GPS tracking collar was working at that time, we were able to locate the cows and collect the observations that we needed.”

“It did allow us to observe a lot more cows calving in a big paddock than would have been possible, simply by observation, and we were able to do it with minimal disturbance.”

Some issues did emerge with GPS Tracker reliability, however, and if the collar wasn’t working it made it impossible to find the cows (or the sensors) after an alert was received. Observations had to wait until they came into a water trough.

The main reasons for the collar failures was due to the extreme high temperatures in the area (daytime temperatures above 40C), causing the antennae to fail, and heating and cooling causing some moisture leakage, despite being IP-rated. The manufacturer has used the information from the study to come up with a new and improved version, which will be used in the next calving season.

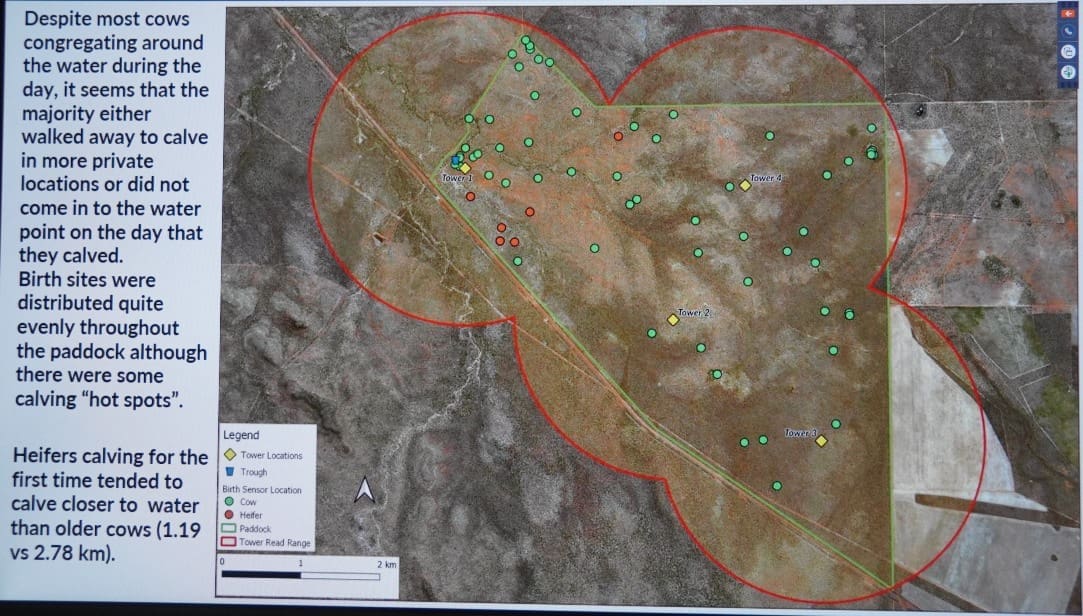

As illustrated in the GPS tracking paddock map below, birth sites – especially in mature cows – were located all over the trial paddock, while heifers tended to calve closer to water. Cows calved 3km from water, on average, while heifers calved just 1.2km from water. One cow (bottom right) calved 5km from the single watering point in the paddock.

GPS data showed the cows were walking between 8km and 11km per day.

Trial results

Despite the tech issues, information was gained on most of the 200 cows within two days of calving, Mr Schatz said.

During the period of calving around November-December the temperature was up around 40C most days, and there was no rain until early December. Because of that, cows were coming into water virtually every day.

Bottle teats was a significant contributor to calf loss

The calf loss in mature cows was 16.8pc – higher than the average loss at the site over the previous four years.

Among 50-off first calf heifers in the trial, their calf loss was very high, at 36pc. However the heifers were shifted while pregnant from an improved pasture areas to the harsher location of the trial.

Among the mature cows in the study, the calf loss was about 6pc higher than the previous four-year average (the paddock has been leased by DPI&R for the past four years) of 10.7pc.

“It is difficult to determine the reasons for the increase, and is likely to be the cumulative effect of several factors,” Mr Schatz said.

These included:

- The very hot, dry conditions, with a late start to the wet, and poorest wet season in 50 years

- The extra activity of observers in the paddock

- Wild dogs were present in the paddock (trail cameras provided clear evidence), but actual evidence of dog attack was quite low at 2.5pc of calves with bite-marks at weaning, compared with an NT average of 6.2pc.

Among other factors, dystocia loss was measured at 1pc (of the overall 16.8pc) in mature cows, but 6pc in heifers. Post-natal loss from bottle teats accounted for 6pc in cows, while neo-natal septicaemia, and infection of the umbilical cord accounted for minor losses. Almost half of the overall losses among cows were due to unknown causes.

“Bottle teats are a bigger problem than previously thought,” Mr Schatz said.

“There are a lot more cows out there in northern herds with problems with bottle teats (which disappear after the calf is weaned or dies) that go undetected. A lot of the cows observed to have bottle teats shortly after calving, looked normal several weeks later.”

Another interesting finding was that 71pc of the sensors were expelled during daylight hours, with the peak between Noon and 3pm.

The trial will be repeated this coming calving season.

HAVE YOUR SAY